#Signage

International research has consistently shown that visibility of minority languages leads to increased normalisation, which in turn, contributes to increased tolerance and understanding of those languages.

Irish here is an important component of our shared heritage and so signage, particularly in our shared spaces, should include Irish; it provides a neutral opportunity for people to engage with the language. It is for this reason that we have held and attended a number of protests, calling for the inclusion of bilingual signs in a number of shared spaces across the north.

Parks

Belfast City Council erected new English-only information signs across a number of their public parks, two of which (Falls Park and Willowbank) are situated in the heart of the Gaeltacht Quarter. The use of English-only signs in the parks within the Gaeltacht Quarter, and indeed, across the greater Belfast area, represented a clear breach of the council’s duties under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, and was at odds with Belfast City Council’s own languages strategy which aims to: “increase the visibility and use of the Irish language in Belfast as appropriate through council services, facilities and events.”

Their English-only approach to signage totally excluded the thousands of Irish speakers who use these services on a daily basis. An Dream Dearg stood with members of the community who challenged this decision by Belfast City Council, and called for the immediate erection of visible information through bilingual signs. The Council agreed to set up a working group of elected members to consider the council’s actions, policies and processes in relation to their languages strategy. As of yet, no bilingual signage has been erected and no working group has been established within the council.

Bilingual signage at Queen’s University Belfast

A rash decision by Queen’s University Students Union to remove bilingual (Irish/English) signage in 1997 has been the catalyst for An Cumann Gaelach’s campaign for the erection of bilingual signage. At the time, the Fair Employment Commission ruled that the bilingual signs were ‘incompatible with a neutral working environment’ and that they created a ‘chill factor’ for Unionists’ within the university.

In 2017, 20 years on from the decision by the Students’ Union to remove the signs, An Cumann Gaelach began their very own campaign. At the beginning of the academic year 2017/18, the new committee held a protest at the gates of Queen’s University and wrote a letter to the vice chancellor, requesting a meeting regarding the promotion of Irish within the University.

‘Provocative, offensive, intimidatory’ signage would not be erected.

Their request for bilingual signage now extended beyond the Students’ Union; they called for bilingual signage throughout the university’s campus. The vice chancellor responded, citing the university’s Equality and Diversity policy that ‘provocative, offensive, intimidatory’ signage would not be erected. This was the exact wording that was used in 1997.

An Cumann Gaelach challenged this decision with a very well-attended protest in February 2018. Within a number of days, the vice chancellor apologised, and a working group was set up to consult on the university’s outdated Equality and Diversity policy, with special reference to Irish.

A member of An Cumann Gaelach’s committee also ran for the position of vice-president of Equality and Diversity in the students’ union elections. Despite the fact that he wasn’t elected, all newly elected members vowed to support the Irish language within the university, particularly through the work of An Cumann Gaelach.

A student referendum found that 76% agreed to the employment of a part-time Irish language officer.

With the help of Queen’s University Student’s Union, a motion was then passed to employ a part-time Irish language officer for the first time in the university’s history. Following this victory, a student referendum found that 76% agreed to the employment of a part-time Irish language officer. In 2018/19, Aodhán Ó Baoill became the first part-time Irish language officer in the university’s history. This was a direct result of the tireless efforts of An Cumann Gaelach.

The end of the academic year 2018/19 saw the draft Equality, Diversity and Inclusion policy of the working group. The new draft policy saw an ever so slight change in wording, with no specific reference to Irish. During the policy’s 2 week consultation period, which falls far short of the 12 week period recommended in the university’s own equality scheme, An Cumann Gaelach once again challenged the university’s exclusion of Irish speakers, submitting a response which called on them to specifically include Irish and bilingual signage in the policy.

This inspiring, transformational student-led campaign has shown that the Irish language community are no longer willing to be treated as second-class citizens.

This response was signed by 1,000 people, from students and faculty alike. The consultation process was then extended, with the results promised before the end of the year. Despite their best efforts, the policy remained unchanged.

This inspiring, transformational student-led campaign has shown that the Irish language community are no longer willing to be treated as second-class citizens. They have promoted their demands for equality in an organised fashion, and have made meaningful and lasting change in an institution which has marginalised our community for so long. Their campaign for bilingual signs and their demands for equality for Irish speakers within the university will continue until Irish speakers have parity of esteem on campus.

City-wide bilingual signage in Belfast City Council Leisure Centres

Belfast City Council decided to erect multilingual welcome signs in all newly-developed council leisure centres, with no mention of bilingual internal signage in any of the buildings.

To put this into context, many children who attend Irish-medium schools make use of the leisure centres’ facilities, particularly for swimming lessons, and are unable to read English. The decision by Belfast City Council meant that they were placing some of their most frequent service users at a disadvantage, leaving them unable to read important directional or safety signage.

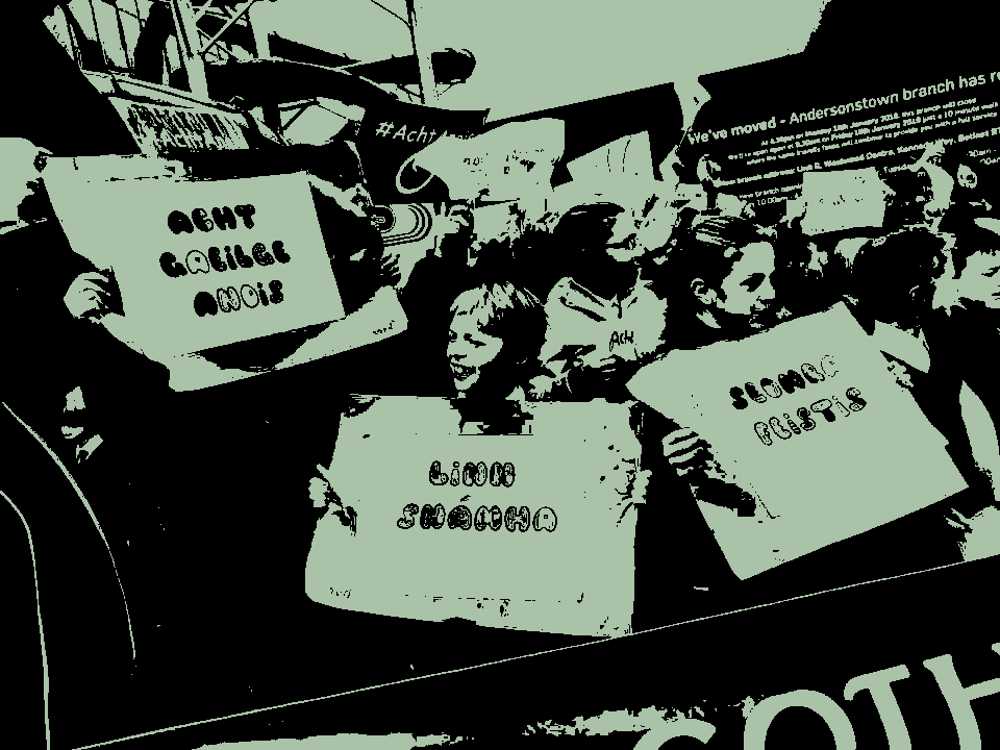

An Dream Dearg, along with children from local Irish-medium primary school, Bunscoil Phobal Feirste, decided to challenge this decision, staging a protest outside the Andersonstown Leisure Centre to call on Belfast City Centre to consider erecting bilingual signs within their leisure facilities to enable children attending Irish-medium schools to read the signage. The council conducted a public consultation regarding the introduction of bilingual signage at the council facilities in 2019. An Dream Dearg promoted the consultation, encouraging people to respond.

The results from that consultation have never been published, but the council eventually decided to erect bilingual signs in the two West Belfast Leisure Centres, Brook and Andersonstown, which are situated in predominantly nationalist areas, leaving Lisnasharragh, Olympia and Templemore leisure centres all without.

It’s important to note that children who attend Irish-medium schools visit these leisure centres too; the closest school in proximity to the Olympia Leisure Centre, for example, is Gaelscoil na bhFál. Irish belongs to everyone. We therefore believe that there should be a uniform approach across all Belfast City Council facilities to ensure that Irish isn’t promoted on one side of the community and alienated on another.

Bilingual signage at University of Ulster

Following a period of campaigning from student activists, a University of Ulster Students’ Union (UUSU) council meeting in November 2018 saw agreement on a bilingual signage policy within the Union. This policy, if passed when subject to further discussion with university senior management, would mean that Irish was to be included on all UUSU signage.

Despite this positive step, the decision by UUSU did not go unchallenged; some of those who were opposed to the decision spoke out, branding the move as a ‘political stunt’ and citing the Union’s Good Relations Policy in an attempt to undermine the progress. This was an example of the university’s good relations duties being deliberately misinterpreted to exclude Irish speakers.

Alienating the Irish language is not the way to make Gaeilgeoirí feel more welcome on campus.

Indeed, despite the vote being taken and subsequently passed by the democratic body of student representatives, Ulster University’s Vice Chancellor was clear in his view that the University “…will not be implementing bilingual signage on our campus facilities” because of the need to create an inclusive, welcoming and open environment for students from ‘all backgrounds’.

But alienating the Irish language is not the way to make Gaeilgeoirí feel more welcome on campus. Where were they to fit in in this ‘inclusive environment?’ Therefore, one year on from that historic decision, no policy was enacted, or even put out for consultation. Therefore, students from Ulster University staged a protest at their Magee Campus, calling for the implementation of that policy, and for respect for the mandate of UUSU.

The protest was attended by various members of Ulster University’s Cumann Gaelach, members of An Dream Dearg, representatives from An Cumann Gaelach QUB, along with representatives from UUSU, political parties and the university faculty alike.

Despite the success of the campaign, which is testament to the work of UUSU and Ulster University’s Cumann Gaelach, the policy has been subject to further delays. No bilingual signs have been erected on UUSU signage, and Gaeilgeoirí at Ulster University are still marginalised.

Bilingual signage at Belfast City Cemetery

Belfast City Council announced their plans to unveil a new £2.8 million visitors centre in the Belfast city cemetery; the state-of-the-art centre includes interactive exhibitions and digital research stations, displaying signage and interactive tools which enable people to learn more about the cemetery.

Belfast City Cemetery is situated right in the heart of the Gaeltacht Quarter, one of the most thriving urban Gaeltachts in Ireland; with the largest Irish-medium secondary school in Ireland just a stone’s throw away and the area surrounding the city cemetery being home to numerous other Irish-medium schools, youth services and organisations, the Irish language community were very much looking forward to exploring this new facility.

If bilingual signage and interactive tools couldn’t be provided in the Gaeltacht Quarter, where the language has bespoke status, what precedent does that set for the rest of the city?

Be that as it may, in April 2022, it was announced that the centre was planned to open with monolingual signage (English-only) and interactive tools being installed throughout. This decision was an insult to the Irish language community and demonstrated that Irish is no more than an afterthought within the Council and needed to be challenged; the Irish language community have consistently had to fight for basic provisions like signage when it should already be part of council policy and practice.

If bilingual signage and interactive tools couldn’t be provided in the Gaeltacht Quarter, where the language has bespoke status, what precedent does that set for the rest of the city?

To this extent, after a brief social media campaign, Belfast City Council agreed to take immediate action, erecting interim Irish language signage in Belfast City Cemetery whilst permanent ones were printed. This decision has been welcomed by the Irish language community, but it does draw attention to the wider issue of an Irish language policy at Belfast City Council. Had there been a policy, this decision would have never been taken; there would have been a clear framework which set out clear guidance regarding council signage, branding and logos.